On the fool's journey

How to be a lion, a weasel, or something in between

Last month I finished The Heart’s Invisible Furies by John Boyne. On a high level the novel is a hero’s journey: we follow the main character, Cyril, as he’s born out of wedlock and adopted by a wealthy family in 1940s Dublin. He grows up as a gay man in a repressive Ireland from which he escapes and, after a long exile, to which he eventually returns.

But Cyril isn’t quite a hero. He spends a lot of his life (understandably) concealing who he is or what he wants. He’s secretly in love with his best friend Julian but ends up marrying Julian’s sister, Alice, after which he flees to mainland Europe without telling anyone. He spends twenty years convincing himself he didn’t cause any hurt.

Despite this, Cyril isn’t an anti-hero, either. He finds love in the Netherlands, saves a little boy’s life, and volunteers with AIDs patients at the height of the epidemic. He has mostly good intentions, but it’s hard to take action if you’ve had a lifetime of hesitation, of self-preservation.

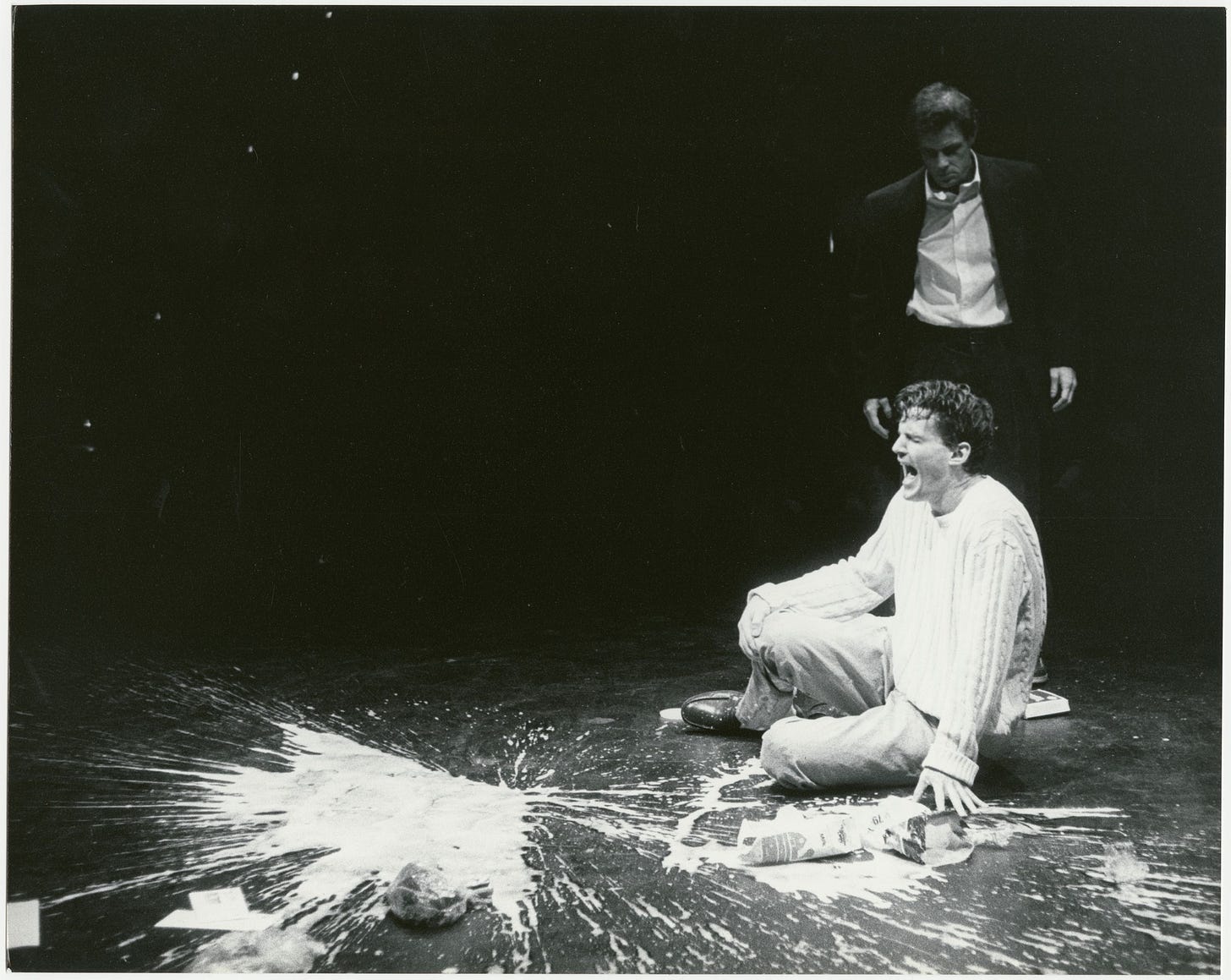

Cyril is simply a fool, like any of us, constructing defense mechanisms to help us survive. And while it’s fun to see a main character who displays courage at every turn, the fool is more compelling. The fool, more than the hero or anti-hero, reflects the parts of us that would rather seek shelter and wait for the rain to pass, float along while others paddle, hold back for fear of even greater calamity.

Ari Aster’s 2023 movie, Beau Is Afraid, is a more explicit depiction of the fool’s journey. Joaquin Phoenix’s character, Beau, is totally helpless in a dangerous world that becomes comically more dangerous every time he defers action, sending him on a dark odyssey where he eventually must face his closest and scariest foe, his own mother, who tells him, “You let things happen to you. Do you think that makes you innocent?”

Witnessing Beau or Cyril continually let things happen to them can be enraging. Just say what you feel! Make a choice! Defend yourself! But in part, pieces like Beau Is Afraid serve as a revelation to just how frightening the world is, how many things could go wrong at any point. It’s a miracle to even leave the house, let alone stand up to your own overbearing mother or tell your best friend you’re in love with him.

Who am I to throw stones? I haven’t left my glass house in years.

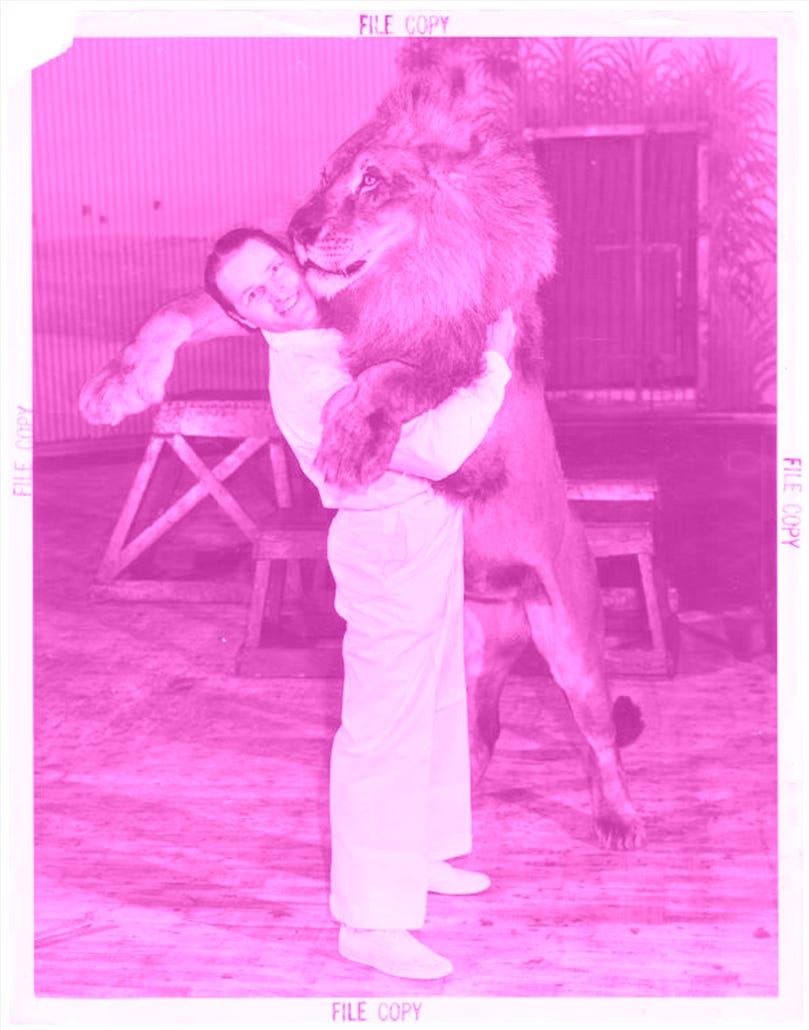

My friend Patrick recently described to me the binary of the lion heart and the weasel heart: the weasel shrinks where the lion steps forward. After a few weasel-heart missteps with people close to him, Patrick wants to cultivate a lion heart, to more directly face challenges. (By his own definition, Patrick’s one of the most lion-hearted people I know, but we tend to be harder on ourselves.)

I thought about a friendship I let go of several years ago, one that was so difficult to deal with head-on that I effectively pulled a Cyril and left without another word. I look back on that decision with ambivalence; I was hurt and afraid and didn’t want to be more hurt and more afraid.

That person still visits me in dreams, where we always reach toward a resolution but never truly find one, and perhaps that’s the penance the weasel heart pays.

While dragging myself through the mud is a fun past time, I’ve largely avoided shameful wallowing about the friendship and instead tried to be more honest when conflicts arise with other people. While it’s flattering to think of myself as someone who doesn’t have needs, doesn’t harbor anger or hold strong beliefs, it just isn’t true.

As a child, I spent a lot of time being whoever adults expected me to be. Nobody had to worry about me if I got good grades, had friends, did my chores. The unfortunate downside to this existence is that I remember every single time I disappointed an authority figure, and each transgression felt like a world-ending event. In sixth grade I wrote a silly, sordid note to a cute boy in my class, my teacher found it, and I made myself sick for days with the shameful thought that she was going to call my parents and I’d be kicked out of school.

Even at a young age, I knew I was just a normal human with flaws and on some level that was fine. That’s part of the original sin, right? But what you show to others — what you show to God — needs to be perfect, somehow. What an impossible task.

As an adult, I’ve had to come to terms with my resentment about this. I spent my early twenties trying to rebel against this perfect standard, smoking, drinking, hanging out with seedy people, hopping jobs. Typical behavior for someone that age, but also a practice that on some level helped me push my flaws to the forefront and still be worthy of redemption, to accept myself as easily as I accepted others.

This scheme worked for awhile but in recent years, as I’ve tried to make more stable long-term decisions, the perfectionism has reared again. It’s always been there; I just spent a decade trying to shove it to the back of my mental storage unit. And now, since I don’t want to smoke or drink or hang out with creeps or leave my job, I have to accept that I’ll fail even when trying to make “good” decisions. It hurts more when you’re committed, and I’ve been eschewing commitment my whole adult life.

If there is one priest who could convince me to be a Catholic again, it is Father Richard Rohr. Though I’d like to stay religiously unaffiliated, I do return to his words often — particularly this sentiment about failure:

“We thought we came to God by doing it right, and lo and behold, surprise of surprises, we come to God by doing it wrong—and growing because of it! The only things strong enough to break open our heart are things like pain, mistakes, unjust suffering, tragedy, failure, and the general absurdity of life. I wish it were not so, but it clearly is.”

So having a lion heart means being broken open, again and again, which Richie Rohr and I both deeply lament. No wonder it takes dire circumstances, perhaps a whole lifetime, to risk the breaking. It’s okay to be afraid. We’ll always be afraid. Sometimes we’ll take the risk despite our fear. We, the perpetual fools, can be once beautiful and brave.

Maybe we don’t have weasel hearts or lion hearts but human hearts, ever oscillating between the two, ever breaking open and attempting to heal.

All images are from the New York Public Library Digital Collections.

If you liked reading this, consider subscribing to get similar thoughts delivered to your inbox on or around the 17th of every month. You probably won’t regret it.